Akira Kurosawa (23 March 1910 — 6 September 1998) is one of Japanese filmmaker easily recognized names in the west, because of groundbreaking shattering jidaigeki period activity films as Seven Samurai (1954), The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Kagemusha (1980).

Read also: Begining with Wong Kar-wai

The suffering prominence of such titles lies in no little part to their open impact from Hollywood, especially the westerns of directors, one of example, John Ford. This in itself is reflected in the simplicity by which they've thus established an action template so promptly adjusted by filmmakers from everywhere throughout the world. Investigate any ongoing historical epic, or in reality the Manichean battle scenes that contain such a large amount of Peter Jackson's Tolkien adaptations, and attempt to envision how they may glance in an imaginary world in which Kurosawa never existed.

The conspicuous impact of these more fantastic titles makes it not entirely obvious the more humanistic, individual parts of the master’s wide cluster of low-key,, contemporary dramatizations and potent literary adaptations. With 30 titles to his name as a director since his 1943 debut Sanshiro Sugata (and a lot more as a screenwriter), refining Kurosawa's must-see titles into a clean top 10 list is something of a boneheads task. There is nothing below average inside this huge and multiple assemblage of work. Numerous commendable title were omitted in the point of giving a more full picture of the products of an extraordinary six-decade filmmaking career.

Akira Kurosawa best movies:

No Regrets for Our Youth (1946)

Motivated by a few real-life incidents, No Regrets for Our Youth is a wise and adjusted show about faltering philosophies and individual devotions set between 1933-46, the long periods of majestic Japan's expanding militarisation through to its wartime defeat.

Read also: Best cinematography in cinema

Yukie is the privileged daughter of a Kyoto University law teacher who is controversially expelled from his post for his radical convictions. The film depicts her relationships throughout the years with two of his previous students, both rival for her love, and her relationship and ensuing marriage with one of them, who is captured for his anti- government exercises and afterward vanishes from public visibility.

Kurosawa's oeuvre isn't especially respected for its attention on sympathetic female characters, yet the focal turn by Setsuko Hara (better known for her work with Yasujiro Ozu) in his fifth feature (and first of the after war time frame) exhibits another side to the director, and furthermore considers his most overtly political work.

Scandal (1950)

The first of two movies Kurosawa made for the Shochiku studio (close by the Dostoevsky transformation The Idiot in 1951), this punchy social dramatization tears into the gutter press, as Toshiro Mifune's best in class painter is snapped by the paparazzi while sitting on an hotel balcony with a well known singer (played by Yoshiko Yamaguchi), the photograph inspiring a fabricated story in a famous gossip magazine. Obviously, the offended craftsman won't accept things lying down and promises to prosecute the magazine's editor.

Rashomon (1950)

The film that propelled Kurosawa's name outside his country (and those of its stars Toshiro Mifune and Machiko Kyo), Rashomon's Golden Lion Award at Venice in 1951 stirred an after war generation of international festival and arthouse audiences to the manifold delights of Japanese film.

Joining two short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, its content also thought outside the box of conventiona film plotting, introducing the idea of the questionable storyteller in its conflicting records of the assault of a samurai's wife as relayed by the key suspects and witnesses to the wrongdoing, including one testimony conveyed from the killed samurai himself by a medium. The breathtaking cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa, and the late-tenth century Heian period setting adds to the eerie, purgatorial feel.

Read also: Top 10 Hollywood directors visual style

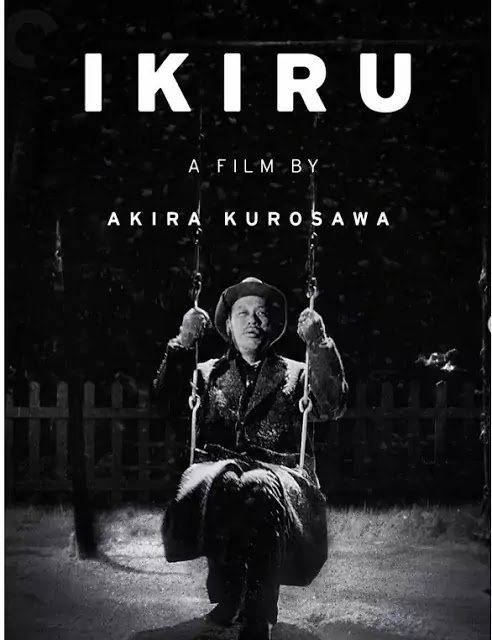

Ikiru (1952)

The story of an undistinguished, time-serving government worker who, after learning he has stomach cancer, channels his energies into one last positive act, constructing a children’s play area in a disease-ridden slum quarter, is really heart-rending. Kurosawa normal Takashi Shimura is awesome as the man who just discovers importance in his life as death pops up, while his in-laws fight over his pension pot. His missing nearness in the last areas gives a more sensible mirror reverse to Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946).

Seven Samurai (1954)

Set during the civil war of the late-sixteenth century Warring States period, Kurosawa's enormously powerful masterpiece portrays a gathering of masterless samurai recruited by a farming community to battle off frequent attacks by a gang of bandits.

Read also: The Ten Greatest feature films of All Time According to 358 makers

The most costly Japanese creation of its day, it introduced all the trademarks related with Kurosawa's name: an epic runtime detailing the recruitment of the hired fighter force, the preparation of the farmers, and the stronghold of the village fully expecting the climactic assault (the first western delivery was cut down from the first 207 minutes); on-location shooting with a solid spotlight on scenes and natural conditions to mirror the internal psychologies of the human elements within them; a meticulous recreation of sets, costumes and weaponry of the period; and parcels and lots and lots of stunning horse-bound battle sequences shot utilizing multiple camera arrangements.

Throne of Blood (1957)

In spite of the fact that the content uses not a single line from its source, Kurosawa's commended transplantation of Macbeth to the lawless realm of sixteenth century Japan considers as a part of the best screen transformations of Shakespeare at any point understood, an unwavering version of the story that works impeccably inside its own authentic setting.

Its title translates literally as ‘Spider’s Web Castle’, and the gothic setting of an abandoned castle loaded up with dark shadows and wrapped in mist shapes the ideal casing for Mifune's tortured turn as Washizu, the samurai usurper frequented by past crimes. The austere staging and performances, drawing upon customary Noh theatre, loan a suitable note of drama to procedures, obscuring the hole between real and the supernatural, while Kurosawa outperforms even himself with the very stunning climax as Washizu's savage offences find him.

Yojimbo (1961)

Mostly propelled by George Stevens' Shane (1952), Kurosawa's quintessential 'samurai/western' Yojimbo ('The Bodyguard') flourishes with this cross-cultural synergy, directly down to the soundtrack. As Mifune's mysterious masterless samurai meanders into a forsaken town invade by rival criminal gangs, the whistling wind whisks leaves down abandoned streets through which a dog runs with a cut off human hand braced in its mouth and the smudged inhabitants, groveling behind shades, dread to step.

The generally humble 110-minute runtime makes this (and its shorter 1962 follow-up Sanjuro) a more available section point into Kurosawa's oeuvre than his more grandiose swords-and-samurai sagas. With Japan's studio system progressively unequipped for obliging the expenses of the long shooting time frames and large-scale sets and action sequences required for his productions, Kurosawa left his studio Toho after Red Beard (1965). Beside independently produced Dodes'ka-lair in 1970 (astoundingly, his first movie in colour), he would not direct another film in his country for a long time.

Dersu Uzala (1975)

With the financial and critical failure of Dodes'ka-den, a picture of the tarnished occupants of a shantytown on the edges of Tokyo, an attempted suicide threatened to put a stop Kurosawa's career. Luckily a greeting from the Soviet Union's Mosfilm to helm this Siberia-set 70mm adaptation of explorer Captain Vladimir Arsenyev's 1923 life account set him immovably back on the international map.

In view of Arsenyev's experiences in 1902 with the older, gnomic, nature-cherishing scout from the nomadic Nanai clan who lends his name to the film (and filled in as a model for George Lucas' creation, Yoda), it sees Kurosawa back in epic structure as the two wrestle against the ice and snow of the steppes. It got the year's Academy Award for best foreign language film.

Ran (1985)

Having a comparative synthesis of psychological tension and stark conventional polish to its more claustrophobic companion piece, Throne of Blood, it is much greater and bolder in desire. With its gathered wide-shots of threatening ranks of horsemen gripping banners assembled on far off hilltops and a standout scene in which ousted warlord Hidetora wanders in a confounded surprise from the whole-world destroying blaze of his assaulted castle, each image is so meticulously created, each scene so impeccably built, as to give the sort of satori snapshots of otherworldly amazement everything except lost in the CG age.

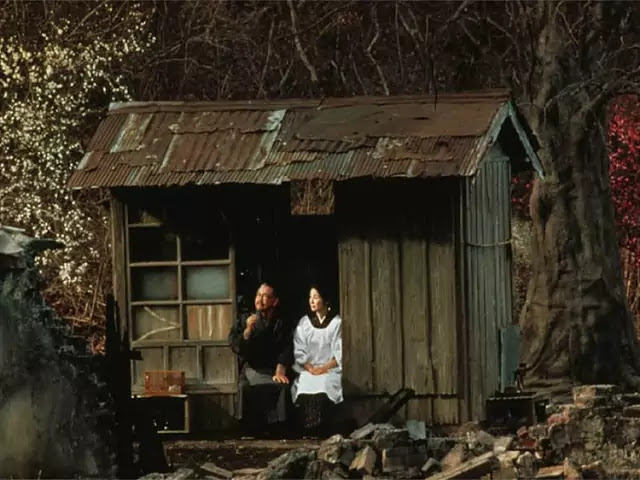

Madadayo (1993)

Without the elaborate action sequences and intense inner dramas for which he is famous, and including an eccentric midriff including a missing cat that keeps going practically thirty minutes, Kurosawa's directorial swansong at first appears to be somewhat disappointing. A portrait of the scholastic and author Hyakken Uchida (1889–1971), unfolding over the decades following Uchida's retirement only preceding the start of Second World War, quite a bit of its runtime is offered over to the optimism going with the crazy annual drinking parties held each year to stamp his birthday by the former students who worship him.

While the relentless verbal punning in the dialogue is at times lost in interpretation (the title, signifying 'Not Yet', implies a legend about an elderly person who will not surrender his hold on life), the noticeable self-intelligent perspective to this festival of a daily existence masterfully carried out in any case has an evident power. The final sequence is as fitting a coda to the amazing career of this legendary filmmaker as one would ever want.

Read also: 92nd Academy Awards thronged controversy

0 Comments